npj Herit. Sci. | The Relationship Between Ceramic Manufacturing and the Development of Social Complexity in the Linfen Basin during China's Late Neolithic Period

China's cultural landscape underwent significant transformations during the Late Neolithic period. Around 2300 BCE, following the collapse of Neolithic societies in the Yangtze River valley, the Yellow River valley emerged as a new center for political experimentation, with Taosi, located in the Linfen Basin of southern Shanxi Province, becoming a prominent political hotspot. The Taosi site has garnered widespread attention from archaeologists globally due to its importance in studying the development of social complexity in Neolithic China. Archaeological surveys and excavations have revealed that during the Late Neolithic, a complex, multi-tiered settlement hierarchy formed in the Linfen Basin, centered around the Taosi site. The increase in social complexity is often accompanied by the emergence of a division of labor and specialized production. As artifacts closely related to daily life, ceramics contain vital cultural information and serve as a key entry point for archaeologists to explore the development of complex prehistoric societies.

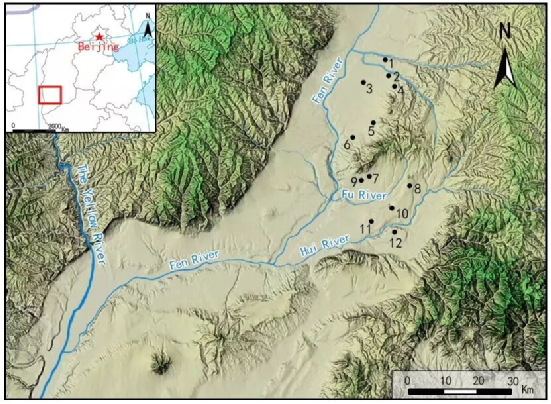

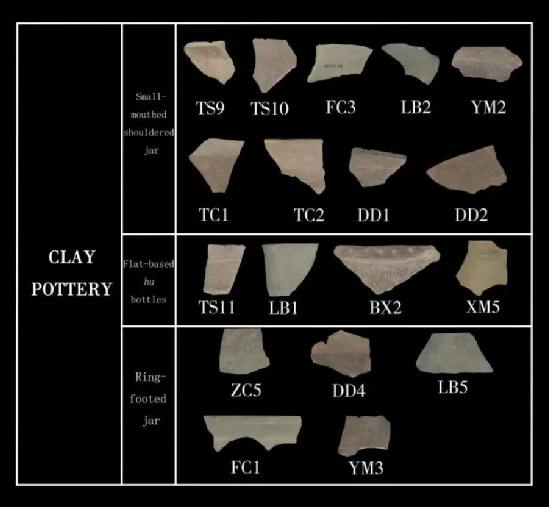

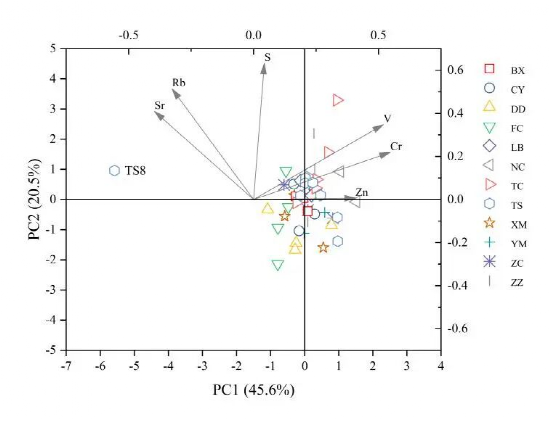

The Center for Archaeological Sciences at Sichuan University has published a research paper in the international journal *npj Heritage Science* titled "Ceramic Manufacturing and Development of Social Complexity in the Neolithic Linfen Basin, China." This study focuses on the ceramic remains from the Linfen Basin, aiming to investigate the correlation between ceramic production and the development of social complexity in the middle Yellow River valley. The paper selected 109 daily-ware ceramic samples from the craft production area of the Taosi site and 11 surveyed Taosi culture sites within the Linfen Basin. Using XRF and ICP-MS analysis, the composition of the ceramic clay was examined. The results indicate a high degree of consistency in the major and trace elements of the ceramic samples, with no strong correlation to site hierarchy or ceramic types. Integrating previous research, this paper suggests that the various Taosi culture sites in the Linfen Basin shared a specific clay source located near the Taosi site.

The large quantities of pottery placed in the elite tombs at Taosi indicate that ceramics were not only important for daily life but also one of the key markers of social status for the Longshan communities in the Linfen Basin. As the most crucial material, the procurement of clay was vital for the success of ceramic production and subsequent use. Considering the social importance of pottery to the Longshan communities of the Linfen Basin, it is possible that clay resources were managed under a central regulatory system, and the possibility of control by Taosi cannot be excluded. Archaeological findings suggest the existence of resource control at the Taosi site. High-value items, such as drums made of crocodile skin, crocodile bone plates, cinnabar, and precious woods, were mostly found in large tombs or high-status buildings. Therefore, specific clay resources may have been controlled along with the aforementioned rare resources, becoming a manifestation of Taosi's political power and statecraft.

Researchers have analyzed ceramics from the Zoumaling Qujialing culture walled site in the middle Yangtze River valley and from Liangzhu culture cemeteries in the lower Yangtze River valley, with results showing different models of clay resource procurement among different regional societies. This study reveals the corresponding situation in the middle Yellow River valley during the Late Neolithic. These different clay procurement strategies reflect the diverse ways of resource acquisition and distribution during the development of social complexity in Neolithic China, offering new insights into the diverse pathways of social complexification in prehistoric China.

The first author of the paper is Huang Lei, a PhD candidate at the School of Archaeology and Museology, Sichuan University. The corresponding authors are Associate Professor Shi Tao of the School of Archaeology and Museology, Sichuan University, and Researcher Gao Jiangtao of the Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS). Co-authors include Zou Luxiang from the Gansu Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, Li Qiang, a PhD candidate at the School of Archaeology and Museology, Sichuan University, and Professor He Nu from the University of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

This research was supported by the Major Project for Developing an Independent Knowledge System of Chinese Archaeology from the Ministry of Education (2024JZDZ055), the National Social Science Fund of China Major Project (22&ZD242), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (scuhistory2024-1).